Comparing the curricula of five teacher education programmes

Written by Maija Simonen.

In 1998, 49 European countries agreed to create a 3-year cycle higher education system with uniform qualifications, which they called the Bologna Process. The purpose of the Bologna Process is to create a European higher education area, and standards and guidelines have been created to ensure that higher education is equal in all European countries (European University Association, 2021). In addition, the European Commission has made common principles for teacher competences and qualifications, which state that teachers should be well-qualified professionals who have graduated from a higher education institution (European Commission, 2021).

My thesis explored how teacher competences can be seen in the curricula of teacher education programmes by analysing these curricula from two Finnish universities (the University of Lapland [UoL] and the University of Oulu [UoO]), two Swedish universities (Umeå University [UU] and Luleå University of Technology [LUT]) and one Norwegian university (the Arctic University of Norway [UiT]).

The aim of my study was to determine which teacher competencies are included in the learning goals of the universities’ educational study modules. I also wanted to compare the structures and learn about the similarities and differences in the curricula in the teacher education programmes of these five universities. My results showed that the programmes differed in structure. For example, in Norway and Finland, teacher education consists of a three-year bachelor’s programme and a two-year master’s programme. In Sweden, teacher education consists of a three-year bachelor’s programme and a one-year master’s programme. I studied all the bachelor’s programmes and the one-year master’s programme in Sweden. The Swedish four-year programme was included because neither of the Swedish universities had a distinct master’s or bachelor’s programme consisting of only either of these.

Therefore, the number of credits was much higher at the Swedish universities (240 credits) than at the Finnish and the Norwegian universities (180 credits). The Swedish teacher education programme includes two branches of study: one prepares teachers for preschool and grades 1–3, while the other prepares teachers for grades 4–6. In Table 1, these two branches of study are marked as follows:

I began by comparing the study modules as a whole. There were significant differences in the numbers of study modules and credits per study module. The curriculum of UoL had the most modules (42), while UiT had the least (12). All the teacher education programmes had modules in basic studies, which in this case included educational sciences, practical training and the subjects to be taught. All the universities except UU had optional study modules, ranging from 25–45 credits.

Table 1 shows the differences between the universities.

Table 1: Study modules in the teacher education programme

|

|

Educational sciences |

Subjects to be taught |

Practical training |

Optional study modules |

Other study modules |

Total |

|

LUT P1–3 |

60 |

120 |

7.5 + 7.5 + 15 |

30 |

0 |

240 |

|

LUT 4–6 |

60 |

90 |

7.5 + 7.5 + 15 |

30 |

30 |

240 |

|

UU |

60 |

150 |

30 |

0 |

0 |

240 |

|

UU |

60 |

150 |

30 |

0 |

0 |

240 |

|

UoL |

25 + 30 (5) |

58 + (2) |

(3) + (5) + (3) |

25 + 5 + 2 |

10 + 25 |

180 |

|

UoO |

25 + 50 |

65 |

(5) |

25 |

15 |

180 |

|

UiT |

30 + 15 |

60 (30) |

0 + 0 + 0 |

45 |

30 |

180 |

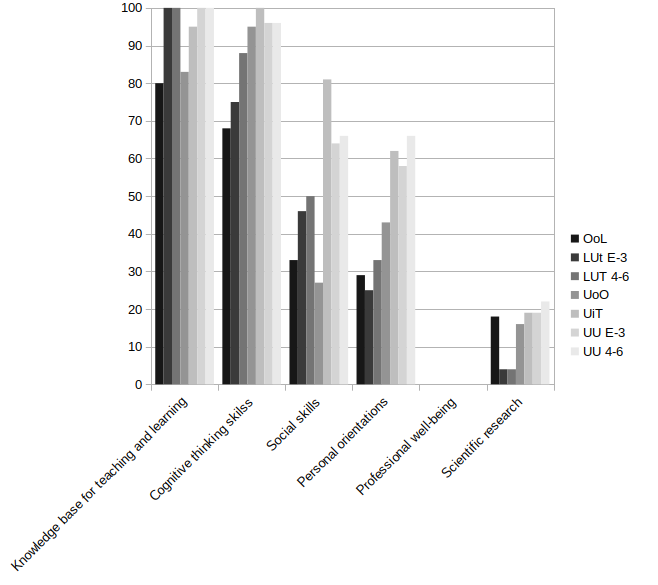

After comparing the study modules, I focused on how the dimensions of competencies can be seen in the learning outcomes of the courses. I used a multidimensional adapted process model of teaching (MAP) (Metsäpelto et al., 2020) as a model to categorise competencies found in the learning outcomes. The original MAP model includes five different dimensions of competencies: (1) a knowledge base for teaching and learning, (2) cognitive thinking skills, (3) social skills, (4) personal orientation and (5) professional well-being. In addition, I created a sixth category, which I named scientific research.

According to the MAP model, a knowledge base for teaching and learning comprises the content knowledge about a specific subject taught in schools, pedagogical knowledge, which refers to the knowledge of managing the classroom, and pedagogical content knowledge, which combines the subject knowledge with how one should teach (Metsäpelto et al., 2020). Almost all the modules in the curricula had learning outcomes regarding a knowledge base for teaching and learning. Only one course in the UiT curriculum and six courses in the UoO curriculum had no learning goals related to a knowledge base for teaching and learning.

According to the MAP model, cognitive thinking skills allow people to critically analyse, solve problems and rearrange and extend knowledge (Metsäpelto et al., 2020). These skills are also relevant in the framework of the qualifications of the European higher education area at the bachelor’s level. The qualifications state that a bachelor’s degree can be awarded to a student who can ‘apply their knowledge and understanding in a manner that indicates a professional approach to their work of vocation . . . have the ability to gather and interpret relevant data to inform judgements that include reflection on relevant social, scientific or ethical issues’ (Bologna Working Group, 2005). Cognitive skills were seen in almost all the learning outcomes of the study modules. UoL had the fewest courses in this competence, and 38% of those courses lacked goals related to cognitive skills. All the study modules at the UiT had cognitive skills listed in their learning outcomes.

The MAP model also includes social skills and personal orientation. These competencies are present in the Profile of Inclusive Teachers, which was written by the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2011). The Profile of Inclusive Teachers is based on four core values: (1) valuing learner diversity, (2) supporting all learners, (3) working with others and (4) personal professional development. In the curricula of UiT, social skills were found in the learning outcomes of 80% of the study modules. For UoO, only 28% of the study modules had no learning outcomes related to social skills. UoO was also the only university that had more learning outcomes related to personal orientation than to social skills. Personal orientation refers to the process of evolving as a teacher. The concept of personal orientation is used here to describe the continuous shaping of one’s self, personality and motivation. UiT had the most leaning outcomes aimed at personal evolution, and 75% of the study modules in its curriculum included personal orientation.

The MAP model also includes professional well-being as a dimension of competence, but none of the universities’ modules mentioned this as a learning outcomes. The sixth category, scientific research, was present in only about 20% of the study modules of all the universities.

In conclusion, this study determined that all five curricula focused on the same teacher competencies. As mentioned previously, almost all the study modules in the curricula had the most learning outcomes focused on having a knowledge base of teaching and learning. All the competencies and how they are mentioned in the study modules’ learning outcomes in the curricula can be seen in the figure below (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Teacher competences in the curricula

Recent studies (Brackett and Katulak, 2007; Uuskylä and Atjonen, 2007) have shown that a teacher needs more social skills and emotional intelligence than cognitive skills. Therefore, it was quite surprising to find that personal orientation and social skills were rarely seen in the curricula.

Notably, this study focused only on the written curricula and only on bachelor’s programmes. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn about the competencies mentioned in the curricula for master’s level programmes.

The writer is about to graduate as Master of Education from the teacher education programme of University of Lapland. The blog text is the maturity text of her Masters’ thesis, where she compared the teacher education curricula of the Arctic Five universities.

References:

Bologna Working Group, 2005. A Framework for Qualification of the European Higher Education Area. Bologna Working Group Report on Qualification Frameworks (Copenhagen, Danish Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation).

Brackett, M. & Katulak, N. 2007. Emotional Intelligence in the Classroom: Skill-Based Training for Teachers and Students.

European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education, 2011. Teacher Education for Inclusion Across Europe–Challenges and Opportunities.

European Commission, 2021. Common European Principles for Teacher Competences and Qualifications.

European University Association, 2021. Bologna Process. Available in: https://eua.eu/issues/10:bologna-process.html

Metsäpelto, R-L., Poikkeus, A-M., Heikkilä, M., Heikkinen-Jokilahti, K., Husu, J., Laine, A., Lappalainen, K., Lähteenmäki, M., Mikkilä-Erdmann, M. & Warinowski, A. 2020. Conceptual Framework of Teaching Quality: A Multidimensional Adapted Process Model of Teaching. Available in: https://psyarxiv.com/52tcv

Uusikylä, K. & Atjonen, P. 2007. Didaktiikan perusteet [Basics of didactics]. WSOY.

Comments